“In 1951, Mohammed Mossadeq, then prime minister of Iran, nationalized the oil industry. In retaliation, Great Britain organized an embargo on all exports of oil from Iran. In 1953, the CIA, with the help of British intelligence, organized a coup against him. Mossadeq was overthrown and the Shah, who had earlier escaped from the country, returned to power. The Shah stayed on the throne until 1979, when he fled Iran to escape the Islamic Revolution.

“Since then, this old and great civilization has been discussed mostly in connection with fundamentalism, fanaticism, and terrorism. As an Iranian who has lived more than half of my life in Iran, I know that this image is far from the truth. This is why writing Persepolis was so important to me. I believe that an entire nation should not be judged by the wrongdoings of a few extremists. I also don’t want those Iranians who lost their lives in prison defending freedom, who died in the war against Iraq, who suffered under various repressive regimes, or who were forced to leave their families and flee their homeland to be forgotten.

“One can forgive but one should never forget.”

-Marjane Satrapi

Paris, September 2002

In the less than two page introduction of the graphic novel titled Persepolis, author Marjane Satrapi provides a succinct synopsis explaining the political and cultural climate of Iran leading up to the Islamic or Iranian Revolution in the late 1970s. Just as she is quoted in writing above, Iran is balled up into many of our western understandings of the Middle East–a discourse that is usually riddled with overtones of violence, religious extremism, terrorism, etc. In the wake of several bloody attacks claimed by ISIS or ISIL just this year, the recent hostage switch in Iran, the Syrian refugee crisis and civil war, and fear-mongering western ideologies, the message conveyed by Satrapi through her autobiographical comic Persepolis is something we need now more than ever.

Generalized news accounts of conflicts, wars, political events, etc., are much more effective and humanized when there is some form of personal account or narrative to supplement with more macro narratives. Take, for instance, the haunting piece of photojournalism that has dominated the covers of newspapers, magazines, and online articles the past week: the photograph of a shocked, silent, and bloody 5 year old boy, Omran Daqneesh, who was rescued from the site of an air raid in the city of Aleppo. His numb gaze is the product of the Syrian civil war. There are many other children like him. Many other children, like Omran’s older brother who died in that same raid, or 3 year old Aylan Kurdi whose drowned body washed upon Turkish shores around this time last year, who are forever silenced. The photographs of Aylan Kurdi and later his morning father started an urgent conversation in Europe regarding the treatment and permittance of refugees fleeing Syria. The parallel between people like Omran Daqneesh’s story and Marjane’s in Persepolis is that readers and viewers can all see the effects of extremism on individual people–people who do not have a say in the trajectory of their own country’s embattlements.

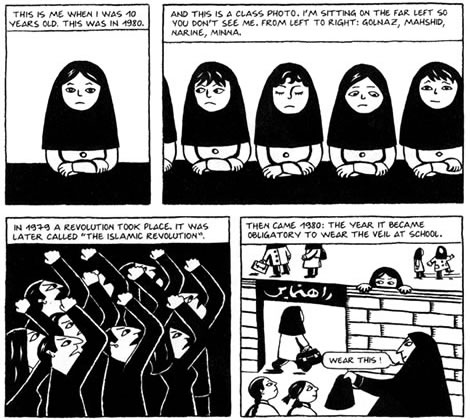

Persepolis is both an autobiography and Bildungsroman. It begins with a young Marji who begins to explain how the revolution in Iran is affecting her and her classmates on a personal level. The great thing about graphic novels is how effectively an image can communicate information in a much more viscerally striking manner. In the image below, Satrapi provides the reader with a snapshot of events that led to the image that many of us attach to Iranian women after the revolution. The veil, or hijab.

As stated earlier, the importance of learning the rich history of certain countries and people is invaluable to our understanding and tolerance toward any given situation regarding human rights, religion, ideology, etc. Perceptions of Iranian people and culture is challenged when we see people like Kimia Alizadeh Zenoorin becoming the first Iranian woman to win a medal at Rio 2016 Olympics. Throughout her Taekwando match and after, she wore a veil or hijab which covered her hair and neck.

The matter of the hijab, chador, niqab, and burqa has dominated recent news stations as well. Over a week ago on a beach in Nice, France, a woman was forced to remove her burqini by four French police officers who were enforcing the recent and controversial ban on burqinis. Burqini is a term used for a type of swimwear that covers the entire body leaving the feet, hands, and face visible, allowing Muslim women to sunbathe, swim, etc., while covering their body. The burqini ban is mandated by French mayors as a result of the Bastille Day terrorist attacks in Nice earlier this summer.

Persepolis provides a context of humanism rather than terrorism when talking about issues dealing with the hijab and other topics related to Islamic cultural and religious institutions. While Marji rebels against the mandated veil because it does not fall in line with her’s or her mother’s beliefs, the floor becomes open for discussion and understanding when reading about a person’s individual experience with the sometimes controversial garment. In Iran, shortly after the revolution gained enough speed to begin mandating certain aspects of Sharia law, Marji is met with the same resistance and oppression that the sunbathing woman mentioned earlier faced when a group of women wearing veils chastises and threatens Marji for wearing her blue jean jacket and Michael Jackson button. In this book, the dichotomous world of right and wrong is surpassed–ultimately providing a space for considering the places in between two dichotomies.

Persepolis is usually catalogued in Young Adult sections of libraries, making way for young people to critically think about and process certain issues that are otherwise glossed over in all-too-predictable and inaccessible dialogue.

Bear in mind that this analysis of Persepolis is coming from someone who was born in 1989. I had no prior understanding or knowledge of Iran other than what has been in the news since I can remember. Persepolis is often times taught in high schools, an environment where students’s perceptions are constantly changing–their minds making room for both fictional and real human experiences.

Persepolis follows young Marji as she grapples with the changes in the political, social, and religious landscape of Iran. Marji idolizes various revolutionists, social theorists, and activists, including her uncle Anoosh who dies at the hands of prison guards of the revolution because he is considered an infidel. As Marji grows older and witnesses the country around her transform into an isolated country ruled by Sharia law, she only becomes more and more resistant to this transformation. She continues to rebel in various forms–from attending protests to wearing “westernized” or “decadent” clothing. Her mother knows how serious the revolution is. In a stingingly memorable part of this work is when Marji’s mother tells her that she is risking being imprisoned and executed. What’s worse, her mother warns her, is that virgins cannot be executed. This means that an imprisoned young woman like Marji would first be married to the leader of the revolution, raped, then executed. In fear of this brutal reality, Marji’s parents agree to send her to school in Austria. While Marji is keen on leaving the Islamic republic and its ideals in her past, she begins to realize that there are still so many aspects of Iranian culture that she is adamant about defending. She sees parts of herself “assimilating into western culture” and simultaneously gains pride in her heritage. Marji falls in love with Reza, moves back to Iran to attend university, challenges many inequitable institutions in her Tehran university, graduates, and, well, you’ll have to read the rest.

Though the images are provided in a stark palette of black and white, Satrapi presents the reader with a story that explores the gray areas. Please give this book a read. In honor of Banned Books week, which is upon us, this book has been challenged and banned in various locations.

Enjoy!

LD

Thanks for this great article! I’m reposting it on our MCPL facebook page along with a picture of the books on our Banned Book display that I put together last week. (Because it’s never too early to read a banned book!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

This blog entry makes me want to get my hands on this book!

Thanks LD!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I liked your book review gave me a lot of details and went over important topics. I’m looking forward to reading all your other book reviews.

LikeLiked by 1 person