By Stuart

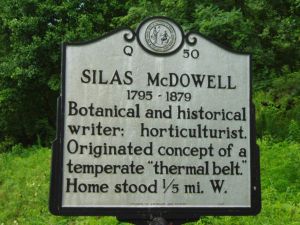

If you’ve ever driven Highway 64 between Franklin and Highlands, you’ve seen the historical marker:

SILAS McDOWELL 1795-1879

Botanical and historical writer; horticulturist. Originated concept of a temperate “thermal belt.” Home stood 1/5 mi. W

What the marker doesn’t say (though an accompanying online essay found here: SILAS McDOWELL 1795-1879

at the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, does) is that McDowell was the genesis for what is generally considered the first “North Carolina” novel—that is, a work written by a Tar heel and set in the Old North State. “Eoneguski: or The Cherokee Chief” by Robert Strange

[You can also read it online here, at the University Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel hill’s digital collection of primary documents relating to the American South—a great resource:]

http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/strange1/menu.html

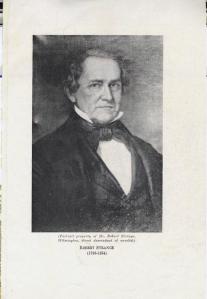

was published, anonymously, in 1839. Strange had first visited the area when he was a circuit-court judge in the 1820s and ‘30s, frequently traveling from his home in Fayetteville to Waynesville, and then to Franklin. This was just 10 years after the Cherokee ceded their lands in what became MaconCounty, and before their forced removal on the Trail of Tears. In Franklin, Strange got to know Silas McDowell, then Macon County clerk of court and an all around intriguing man, interested in just about everything. The wonderful Franklin Press columnist and former editor Barbara McRae has much fascinating info on the genesis of “Eoneguski” at her web site http://www.teresita.com/. (Indeed it’s thanks to Ms. McRae and Smoky Mountain News contributor George Ellison that I learned about Silas McDowell and his contributions to our state’s literary and natural histories.) He deserves a post all his own, but now I’m concentrating on Mr. Strange.

The author, in a framing device for the novel, before the story proper opens, says he heard his tale from McDowell, whom he calls “Mr. McDonald” in “Eoneguski.” A sympathetic innkeeper in town brought the two men together. The encounter is a charming picture of life in early MaconCounty:

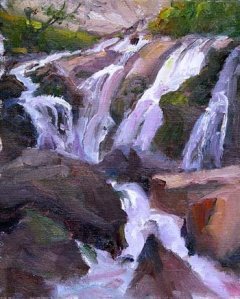

“A few years ago I was a traveller through the western part of North Carolina, and having stopped early in the evening at a small village, on the southwestern side of the Tennessee River, in the indulgence of a curiosity common to myself, with most travellers, I inquired if the neighborhood furnished anything to gratify an admirer of the works either of nature or of art. My host, who was, by the way, an amiable and intelligent man, promptly answered, that there was within the limits of the village itself, an “Indian mound,” and that the Falls of the Sugar Town Fork [the lower falls of the Cullasaja River], a few miles distant, were esteemed quite an interesting spectacle to such as loved to see nature in wildness and grandeur [and] he kindly offered to accompany me the next day as far on the way to the Falls as the residence of Mr. McDonald, who was, he informed me, the clerk of the court–a scholar, a gentleman, and one deeply versed in the legendary lore of the country, which he took great pleasure in imparting whenever it was his fortune to meet with an intelligent and interested listener.

When I entered the house of Mr. McDonald it was not with the feelings of a stranger; his first salutation being sufficient to satisfy me that he was a man after my own heart. Had he lived in a city, he would have been a book-worm, and wasted all his means in acts of benevolence; but in his present situation, with a scanty library, he was forced to read the book of nature, or, at least, many of its most striking pages; and the demands upon his generous feelings were few, and never such as to tax the pocket….

In a short time Mr. McDonald and I were ready to pursue our way, leaving my host of the village to return at his leisure. An hour’s riding brought us where Mr. McDonald informed me our horses could no longer be useful; we accordingly tied them to a limb of a tree, and began, on foot, to encounter the very steep ascent formed by the mountains so closing in as to leave only a very narrow pass for the brawling stream. After laborious climbing for another hour, we reached the Falls, which, I confess, disappointed me, and I was even so impolite as to acknowledge it to my guide. But the wild and picturesque scenery through which I had passed, would have repaid me for my fatigue, had I found nothing more.”

Strange—or as he calls himself on the title page, “An American”—must be among the handful of people not to be impressed by these magnificent falls. In any event, he then confesses to “an especial relish for good eating and drinking” and what came next more than made up for the trek up the rocky Cullasaja. “As we turned to descend—‘We must take a salmon home with us for dinner,’ said Mr. McDonald.

‘A salmon?’ said I, in unfeigned surprise.

‘Yes,’ replied my host, in his quiet way, ‘a salmon.’

‘You are jesting with me,’ said I.

‘Indeed I am not,’ said Mr. McDonald, deliberately seating himself by the side of the stream we had regained, and pulling off his coat, shoes and stockings, and rolling up his pantaloons and shirt sleeves.

In a moment more he was in the water, turning over the large rocks, with as much earnestness as if he had expected to find a bag of gold beneath each of them. I looked on, puzzled what to think of my new acquaintance. At length he succeeded in slightly shaking a very large rock, which defied all his efforts to turn it over, when instantly there dashed from beneath it what, at first, appeared to me to be a perfect monster. Mr. McDonald immediately rushed in pursuit, and a more amusing spectacle I never witnessed for twelve or fifteen minutes. The water was splashed about in every direction, so as to leave not a dry garment upon the pursuer, as a large fish darted from one hiding place to another, with fruitless efforts to avail himself of it. Sometimes the hand of the extraordinary fisherman was fairly upon him, but the lubricity of his scales would save him, and afford him another chance for escape. At length, however, when nearly exhausted with his bootless exertions, Mr. McDonald succeeded in dexterously thrusting his hand into the gills of the fish, which now lashed the water into a perfect foam, and sent the spray in every direction, like a shower of rain. But the relentless foe held on, with tenacious grasp, and dragged him to the shore. My assistance now seemed necessary to prevent the captive from regaining his native element, so completely had the captor expended his strength in the double labor of turning over the rocks to dislodge the game and securing it afterwards.

As soon as Mr. McDonald had sufficiently recovered himself, we repaired to our horses, with our prize, which he fastened behind his saddle. We then proceeded to his house, where Mrs. McDonald prepared for us a most sumptuous dinner, of which the captive fish constituted an important part, and was, by far, the finest, both in looks and flavor, I had ever tasted…I am an admirer of good wine, and consequently have no great relish for what is commonly called native wine, but that which my host furnished on this occasion of his own vintage was to me uncommonly palatable.

After dinner my friend began to exhibit his propensity for legendary recital, and, among other things, inquired of me if I had ever been at Tesumtoe [Tessentee]? To this I replied in the negative. ‘Then,’ said he, ‘you have never seen the plain black cross which marks the head of a grave in the village graveyard.’

‘Of course not,’ said I.

‘Around that cross,’ said he, ‘clusters some of the most interesting incidents connected with this part of the country.’

I encouraged the mood of my friend, and, with short intervals for sleep, and our necessary meals, it was far into the next day when I was compelled to break off, much against my will, leaving his recital unfinished. I returned to the village that evening, and the next morning resumed my journey.” “Eoneguski” is, supposedly, based on McDonald’s—I mean McDowell’s–recital or recounting of “the most interesting incidents” mentioned above.

If you like James Fenimore Cooper, you will love Robert Strange. Alas, most readers now find Cooper’s long-winded writing to be antiquated and hard going—and it can be, as can “Eoneguski.” Indeed, it took me two tries before I really got going and read the whole darn thing, but was glad I did. I think anyone interested in our regional history will, if they are patient, find that it is worth the longueurs. Because underneath the dense, Latinate prose of the novel is a crackling plot struggling to get out. It takes place between WilkesCounty and the headwaters of the Little Tennessee River, near present-day Otto and Franklin and involves revenge, mistaken identities, magic, love across racial lines, Andrew Jackson and the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Many of the characters are based on local historical personages and if the author’s sentimentality gilds the lily, still it is a beautiful mountain lily underneath.

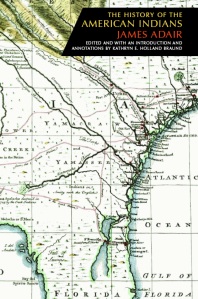

The title character is—probably—at least partly based on Yonaguska (Drowning Bear) who has more recently featured as a character in literature in Charles Frazier’s “Thirteen Moons.” His home is the Cherokee town of Eonee (Strange’s name for Nikwasi, the site of present-day Franklin) where his father is chief. In real life Yonaguska was the adoptive father of Will Holland Thomas, the white chief of the Cherokee and Confederate colonel, and the inspiration for Charles Frazier’s novel “Thirteen Moons.” Eoneguski’s white protagonists, the Aymors, are based on the Love family (amor is the Latin root of amour or, in English, “love.” Get it?), early settlers in Waynesville. Strange’s thrilling accounts of Indian pursuit and fighting could have come right out of james Adair’s “History of the American Indians.” (Adair was a Scotsman who had a Cherokee wife–among others–and who lived as a trader among the tribe in the 18th century.)

His descriptions of the local landscapes in springtime are poetic and spot on, as anyone who drives from Waynesville to Franklin on Route 441 will recognize: “…the Balsam towered above them in dark majesty, generally throwing its shade upon the stream [Scott’s Creek], which, now and then escaping into bright sunshine, sparkled, as in delight to feel the genial warmth.” On reaching the summit of Cowee Mountain [the Macon/Jackson county line] “the Tennessee Valley was spread out before them [and] mountain beyond mountain rose in thick array, [their] silvery brightness borrowed from the snow with which they were crowned…As they descended towards the valley the air became still more mild, and Gideon Aymor remembered the promise of Eoneguski, that ‘here he would find the game more plenty, and the sun would shine more brightly.’” And so it does on our side of the Cowees.

Strange was elected by the state legislature to be one of North Carolina’s senators in Washington in 1836. He held the office for four years before returning to Fayetteville to resume his career as lawyer and judge.

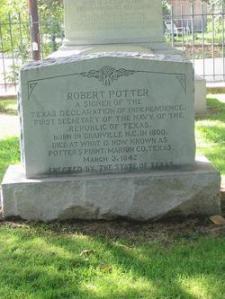

Perhaps the most notorious case over which he presided –before his senate term–was that of North Carolina Congressman Robert Potter (1800-1842). He was accused of a crime so heinous that in the fullest biography of Robert Strange that I could find, the 1852 “Biographical Sketches of eminent American Lawyers, now living” the book only refers to “an offence unheard of in the annals of North Carolina criminal law up to that Time” but refuses to say what it was. Further digging on the internet brought forth the information that Potter believed, erroneously, that his wife was having an affair with not one, but two of her distant relations. Home from Washington, Potter tracked both men down—separately—and castrated them. Miraculously, they survived, but “Potterizing” entered the local lexicon that was usually reserved for farm animals. The jury found the congressman guilty, but as there was no statute addressing the situation, all Judge Strange could due was sentence him to two years imprisonment and fine him $1,000. The North Carolina assembly rushed to make Potterizing a capital crime during its next session. I’m happy to tell you that until this day, Potter remains the only sitting representative of the U.S. Congress to ever be convicted of castrating a man.

After he got out of jail, Mr. Potter moved to Texas, where he became that transitory republic’s first secretary of the Navy. But he didn’t die in bed. According to a later newspaper account that ran in the San Angelo Standard-Times, Sunday, 5 January 1986:

After his tour of duty as Navy Secretary, Potter became one of the most powerful members of the Republic’s legislature. He moved to Potter’s Point, on CaddoLake near the San JacintoRiver. Potter was a moderator in the regulator-moderator conflicts in East Texas. The moderators were opposed to the vigilante tactics the regulators used in attempting to impose their will in no-man’s land of far EastTexas, including Potter’s Point.

One morning in March 1842, a group of regulators surrounded Potter’s house. Harriet [who considered herself Mrs. Potter, though she was really Mrs. Page] tried to get him to stay in the house and shoot it out, but Potter thought his chances were better if he made for the lake and swam out of harm’s way. He raced through a hail of gunfire to the lake, while Harriet searched in vain for matches to light the small canon Potter kept for home defense. He dived in and swam as far as he could. When he broke surface, he was immediately shot through the head. A regulator turned to Harriet and said, “How do you like your pretty Bobby now?” Harriet and friends searched for two days on the lake before finding the body. She found the matches in Potter’s pocket.

The Fontana Regional Library’s editions of Eonegusky are a 1960 facsimile of the 1839 edition, and difficult to read because of the poor print quality. If money and time allowed, I would love to see a new, annotated, scholarly edition with handsome printing and illustrations. The novel is not just a literary antiquity, but a treasure. And, even though Robert Strange died and is buried at Myrtle Hill, his plantation outside of Fayetteville, one of his direct descendants lives in Cashiers, where she is an active and generous member of the Friends of the Albert Carlton Cashiers Community Library, and a fine novelist in her own right.

Stewart, I loved this post about my great- great grandfather. Thank you. Although I own a copy of his novel — rather, the facsimile — unlike you I have never braved the antiquated typeface. I will give it another try because of your writing. Fascinating how much misinformation I have about Robert Strange.

I took my mother, who was on her late 80s, to visit the Fayetteville home of Strange and was sadly disappointed to see a quite modest, rundown house,

of zero architectual interest, but not disappointed by the generous welcome from its present owners nor by the spectacular welcome and hospitality we were shown by a dozen cousins and kinfolk unknown to us until a few days earlier when I had phoned various places in Fayetteville to find out if there was a house or anything in town that had belonged to Robert Strange that we could visit, and a young girl answered one call by saying that she didn’t know anything about him, but her grandmother would because she was his great granddaughter.

He is buried in the back yard of the house. The lid of the grave is a slab of cracked concrete. It made me rather sad. A few years later, however,

Jack Edwards, who has a summer home at High Hampton and who was a United States Representative from Alabama for many terms, gave a talk at our Cashiers library about his years as a Congressman. He told a number of funny anecdotes — I suspect there must be a book entitled ” Congressional Anecdotes for Speeches” — and one he told was of a congressman who was buried in the back yard of his home. No name on the grave. Only the words “An Honest Man.” There was no need for a name, Jack said, because anyone who saw the grave and knew a congressman was buried there, would murmur. “An honest man? Strange.”

Thank you so much, Stewart.

Marilyn Dorn Staats

LikeLike

Wow, I hope Mr. Strange was paid by the word!

(Note to Regulators: I always keep a Zippo next to my home cannon.)

LikeLike